My in-person photo workshop starts next weekend, to be held over six Sunday afternoons. As I write this, I’ve got two slots available. Please spread the word. If you or someone you know is interested, I’d love to have you. More info is here.

Came across the above photo while setting up for my workshop. It’s from a 2001 collaboration in Minsk I conceived with Karel Cudlin and the late Uladzimir Parfianok. We seem pretty relaxed, must have been maybe a day or two before our joint exhibit opened *on 9/11*. It was the Czech cultural attache who - soon after the US embassy guy abruptly stopped talking to me and dashed from the gallery - told me ‘planes are hitting buildings’ in the US.

It was a modest endeavor but our goal was more grandiose - establishing the documentary photography tradition in post-Soviet Belarus. The idea of photographers as sensitive, critical, humanistic observers, especially in repressive societies. Documentary photography was not well-known there at the time, due to their history there was state-controlled media photography, a bit of conceptual fine-art photography, and not a lot in-between. We tried to nurture the basic idea that photographers should be out there showing their reality in expressive ways.

And it worked.

Over the next ten years or so a young generation of photographers did emerge. I’m not saying we did that entirely, it could have happened organically anyway, but I know we planted seeds. I’m not sure we could do it today, the repression is much worse there now since the clampdown following the 2020 election. Yes, back in 2001 there was the KGB and bad things could happen to you, but if you weren’t political (as I wasn’t) you could do a lot. I even had sympathetic state media coverage of one of my solo exhibitions there, probably because it was exotic that an American even cared about everyday Belarus.

I don’t think I would (or could) set foot in Belarus these days, sadly. Uladzimir, my late curator friend who organized our shows and collabs, once smiled and told me Belarus was more of a ‘soft’ dictatorship. Certainly much harder now. In a way, working there showed me so much about how repression takes root but how resilience does as well.

Never thought the lessons would feel so pertinent.

In Nairobi I did something similar. I held a photo workshop for young photographers from the huge Kibera slum, who are carrying the torch for telling their own authentic stories both in Kibera and fast-changing Nairobi in general. They are the new wave of Kenyan storytellers, working from the inside, developing their own visual vocabulary. We’ve become friends, I continue to mentor a few of them and I’m sure we’ll keep looking for ways to collaborate.

I’m about to launch a new workshop series here in the US, a compression of my past teaching curriculum. Not that we don’t have plenty of photographers, we certainly do. And a strong tradition of documentary, including the Farm Security Administration photographers that fanned out across the country during the Depression. Still, as I been posting over the last two weeks, I believe what’s needed is a reboot of photography’s purpose, based on personal authorship, in our age of overwhelming image saturation and looming AI.

The photobook reading room is part of my new workshop space

In Belarus, it was about reflecting a country in a moment not just of repression but identity crisis following the end of the Soviet Union. In Nairobi, notoriously difficult to penetrate (for example until not long ago it wasn’t even legal to photograph on the street without a permit), it’s a matter of getting the real stories from a growing African city with an increasingly glossy image but a massive gap in who that growth helps.

In the US it’s a somewhat different task in a different moment. Photography can be about reclaiming our agency, as so many forces are conspiring to smother us, numb us, and detach us from life. Not just the turn toward authoritarianism but more generally consumerism, conformity, and our dependence on screen-life.

Deeply reconnecting with real life and our surroundings - and even our inner selves - could be revolutionary. As I’ve written, photography can help do that. It relies on those connections and it’s a natural remedy for much of what ails us. In a way it’s a question of rediscovering photography’s unique potential but also how to carry it forward in new ways.

Happily, developing those personal connections is also the way to make your pictures better. Making them more you.

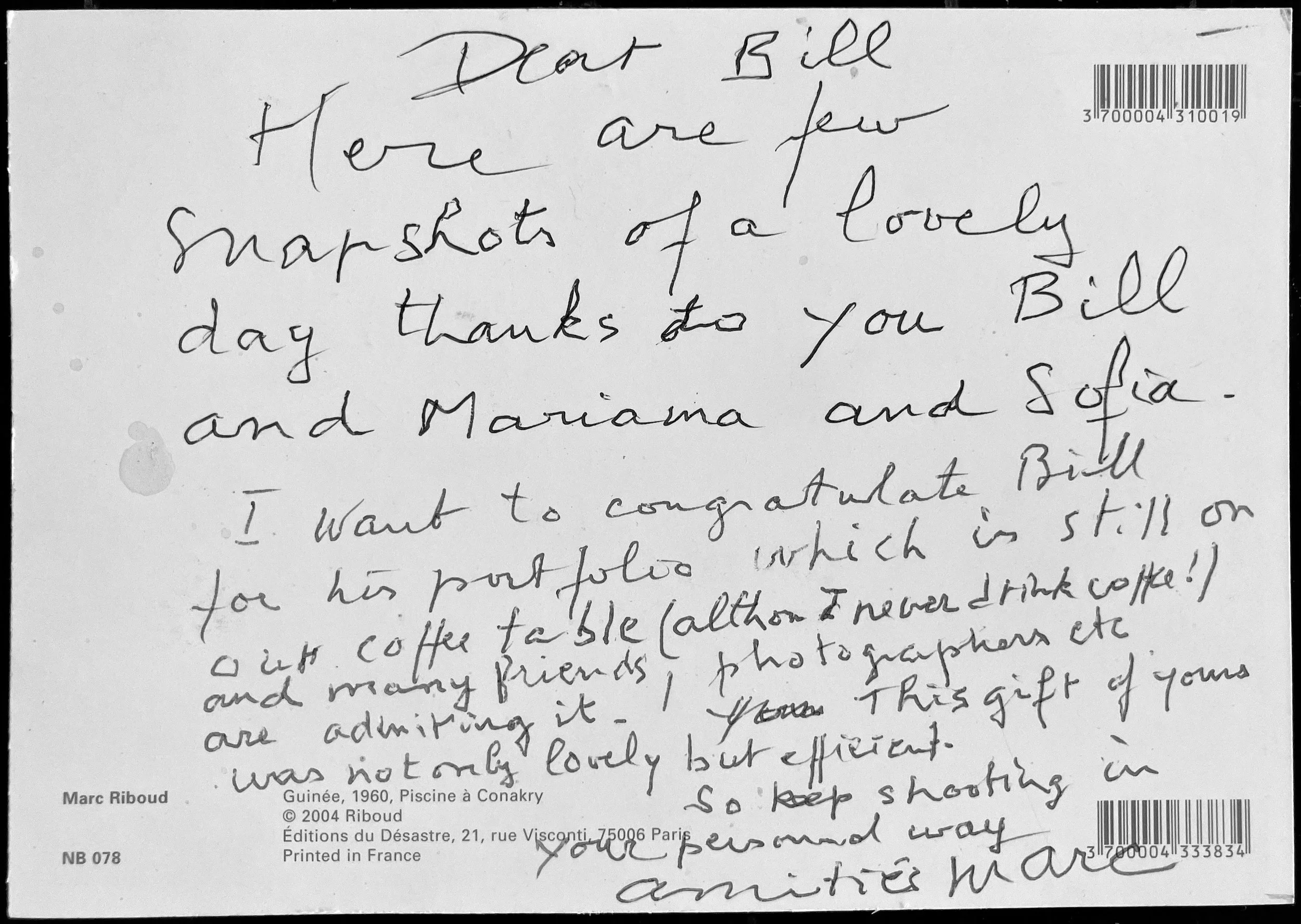

In a way I’m paying it forward for those who helped me do the same. While getting the workshop space ready - and going through a ton of odds and ends since getting back - I found postcards I received long ago from my own photo mentors, encouraging me in my strivings for a more personal vision. One is from the legendary French photographer Marc Riboud in 2007, before he passed away a few years ago. My wife and I had been lucky to become friends with him, this is from after visiting him in Paris with our then-infant daughter:

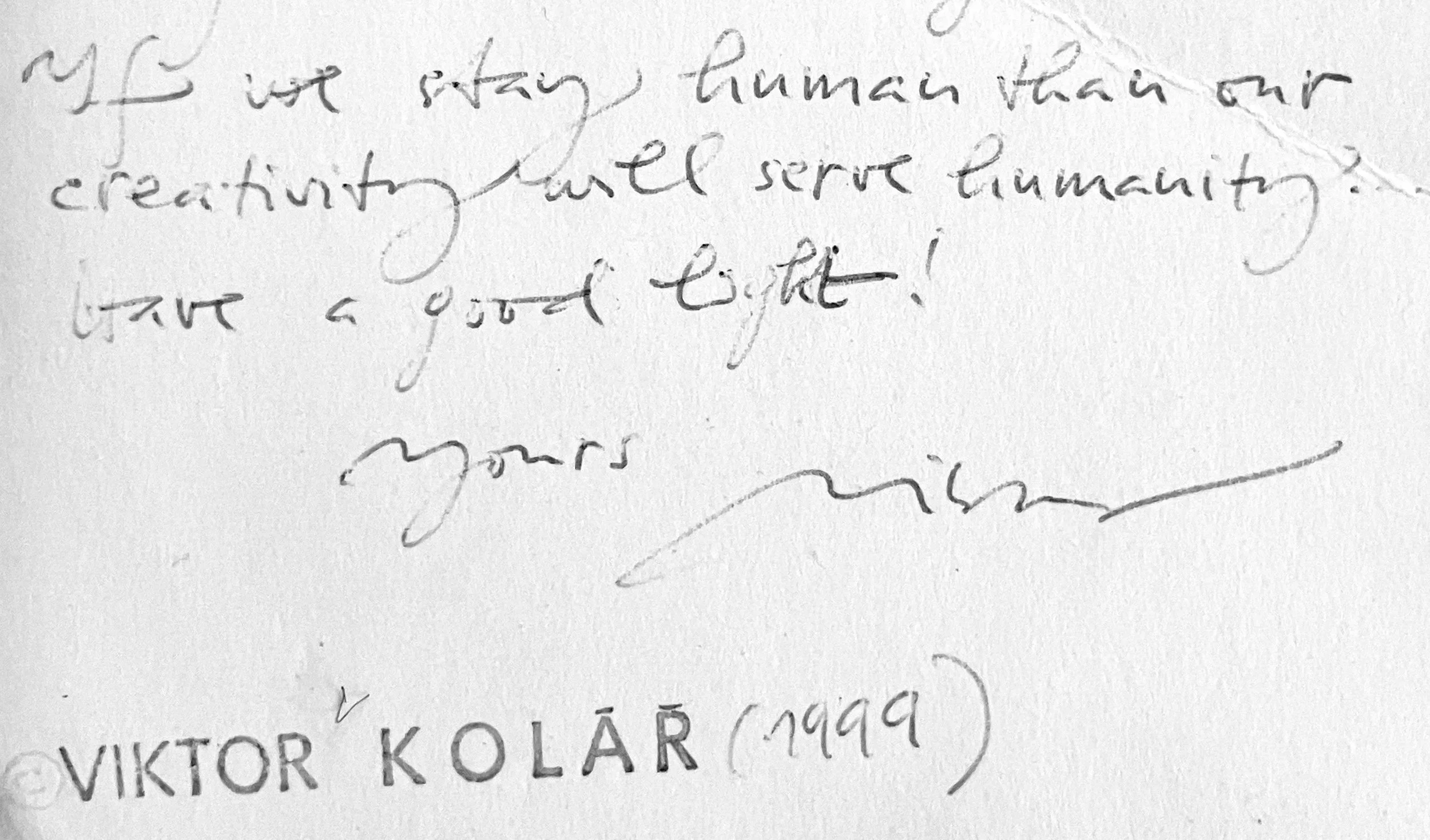

The other is from the great Czech photographer Viktor Kolar, who I had met in Prague when I was first seeking my own transition from photojournalism to a more personal approach. As always, he put it best.